The Constitutional Commission of Congress, in the Spanish Parliament, gave its approval, at the end of last month, to a new statute that is about to make the Canary Islands legally the first Spanish autonomous community with its own recognised sea, something that has always been outside the delimitation of autonomous regional responsibility, including those regions formed by islands.

The Constitutional Commission of Congress, in the Spanish Parliament, gave its approval, at the end of last month, to a new statute that is about to make the Canary Islands legally the first Spanish autonomous community with its own recognised sea, something that has always been outside the delimitation of autonomous regional responsibility, including those regions formed by islands.

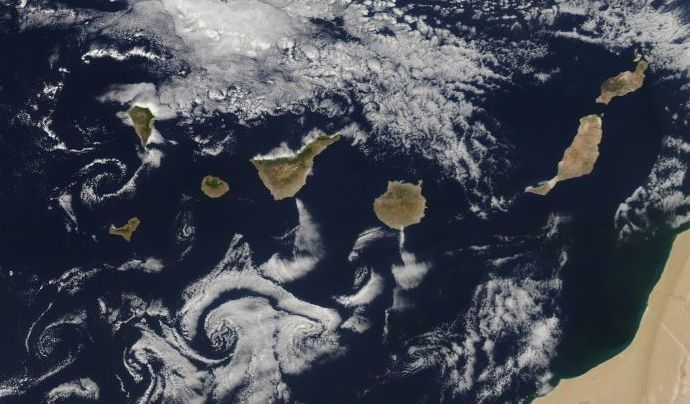

“The spatial scope of the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands comprises the Canary archipelago, composed of the sea and the seven islands with their own administration of El Hierro, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, La Gomera, Lanzarote, La Palma and Tenerife, as well as the island of La Graciosa and the islets of Alegranza, Lobos, Montaña Clara, Roque del Este and Roque del Oeste “, says article 4.1 of the new law.

Of course, also this summer, the number of islands that make up the Canary Archipelago grew, as La Graciosa has now been officially recognised as the eighth island in the archipelago.

In the past it has always been asserted that autonomous communities do not and cannot have sea, not even the Balearics or Canary Islands, whose territory is defined by definition and in their entirety by the water that surrounds their islands, which has been seen as administratively troublesome from a legal standpoint and difficult for citizens to understand, however the Spanish Constitutional Court (TC) has made this standpoint clear in at least four sentences over recent years, all in response to regional government claims against laws or decrees of the Spanish State.

The recent governments of the Canary Coalition (CC) have for several legislatures been leveraging a legal concept, that of the ‘Canarian Sea’, which they have sought to invoke every time they have called into question of formally considered the autonomy of the powers granted by state decisions, whose scope of application was that which begins where the coastline ends. Basically, according to Madrid, the powers of the Canary Islands regional government stop at the coast, leaving maritime issues totally within the control of the Spanish national government. It is an old lawsuit, but one that was exacerbated a few years back when oil prospecting was authorised, against islanders’ wishes, by the Council of Ministers during the first term of the now dethroned Spanish Prime Minister Rajoy.

The recent governments of the Canary Coalition (CC) have for several legislatures been leveraging a legal concept, that of the ‘Canarian Sea’, which they have sought to invoke every time they have called into question of formally considered the autonomy of the powers granted by state decisions, whose scope of application was that which begins where the coastline ends. Basically, according to Madrid, the powers of the Canary Islands regional government stop at the coast, leaving maritime issues totally within the control of the Spanish national government. It is an old lawsuit, but one that was exacerbated a few years back when oil prospecting was authorised, against islanders’ wishes, by the Council of Ministers during the first term of the now dethroned Spanish Prime Minister Rajoy.

The Constitutional response has always been the same, even after Congress approved the so-called “Canaries Water Law” (44/2010), which did not alter in any way the official management of the sea that surrounds the islands. In those judgements, the TC ruled that “the sea is not part of the territory of the autonomous communities” in the Spanish legal system, nor the marine subsoil.

The Canarian Government even appealed to a higher standard, the 1982 International Convention on the Law of the Sea, also known as the Montego Bay Convention, which recognises archipelagos’ competence over the waters that surround them. However, both the central and the Constitutional governments have always responded in the same way: the Montego Bay Convention applies to States that are archipelagos, not regions of a country.

If the plenary session of the Congress definitively approves the Statute of Autonomy at the end of this year, the Canary Islands will now have its own officially recognised sea, to an extent delimited by “a perimeter contour that follows the general configuration of the archipelago”. The integrated waters within this perimeter contour will receive the formal name “Aguas Canarias” (Canarian waters).

This, it is foreseen, will help to put an end to disputes over who has competence or control of the maritime environment directly around the islands themselves, and should put pay to certain absurdities, such as the sea between Gran Canaria and Tenerife being demarcated as international waters.