Special Report

Timon .:.

Without being overly sensationalist, it would be fair to say that, a perfect storm has been brewing for some time in Western Africa. The Canary Islands is a region on the frontier, and needs to avoid allowing fear to drive decision making.

The war in Ukraine may seem very far away, however the disruption to global cereal supplies, those blocked in Black Sea ports, or worse still not harvested all, is adding a growing food crisis to the problems that already existed. There are reports this is now beginning to fuel riots and social unrest in the Sahel, putting at risk the difficult balance that has been maintained over the last two years or so. These problems are not new.

Feature Image

© UNOCHA: Michele Cattani

A young woman carries water in a camp for displaced people in Tillaberi region, Niger.

Food shortages in this vast arid region, which includes Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria, could easily become the final straw for several populations already suffering extreme hardship, and ever-increasing water poverty, as well as the active presence of jihadist groups looking to control resources and establish North African strongholds, which in turn attracts Russian mercenaries, like the Wagner Group (a secretive military organisation who prop up enfeebled governments often suffering from corruption themselves, in return for vast wealth and natural resources, and who, though they claim to be independent, in fact have very strong proven links to the Kremlin). Then there are the various types of organised crime that flourish in such environments. All of which gives rise to extreme circumstances, including forced displacements of native populations, and violent conflict.

Food shortages in this vast arid region, which includes Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria, could easily become the final straw for several populations already suffering extreme hardship, and ever-increasing water poverty, as well as the active presence of jihadist groups looking to control resources and establish North African strongholds, which in turn attracts Russian mercenaries, like the Wagner Group (a secretive military organisation who prop up enfeebled governments often suffering from corruption themselves, in return for vast wealth and natural resources, and who, though they claim to be independent, in fact have very strong proven links to the Kremlin). Then there are the various types of organised crime that flourish in such environments. All of which gives rise to extreme circumstances, including forced displacements of native populations, and violent conflict.

Economic paralysis caused by the pandemic has been compounded by the withdrawals of international support troops, cuts to funding for NGOs on the ground, runaway inflation, unpredictable harvests ever more pronounced due to climate change, high population growth rates (between 2.8% and 3.8%) and growing hunger. The UN have warned of the coming “Unprecedented Hunger Crisis”

Once again, as happened in 2019 and 2020, various organisations and institutions are now warning that a new wave of migration will be headed towards Europe.

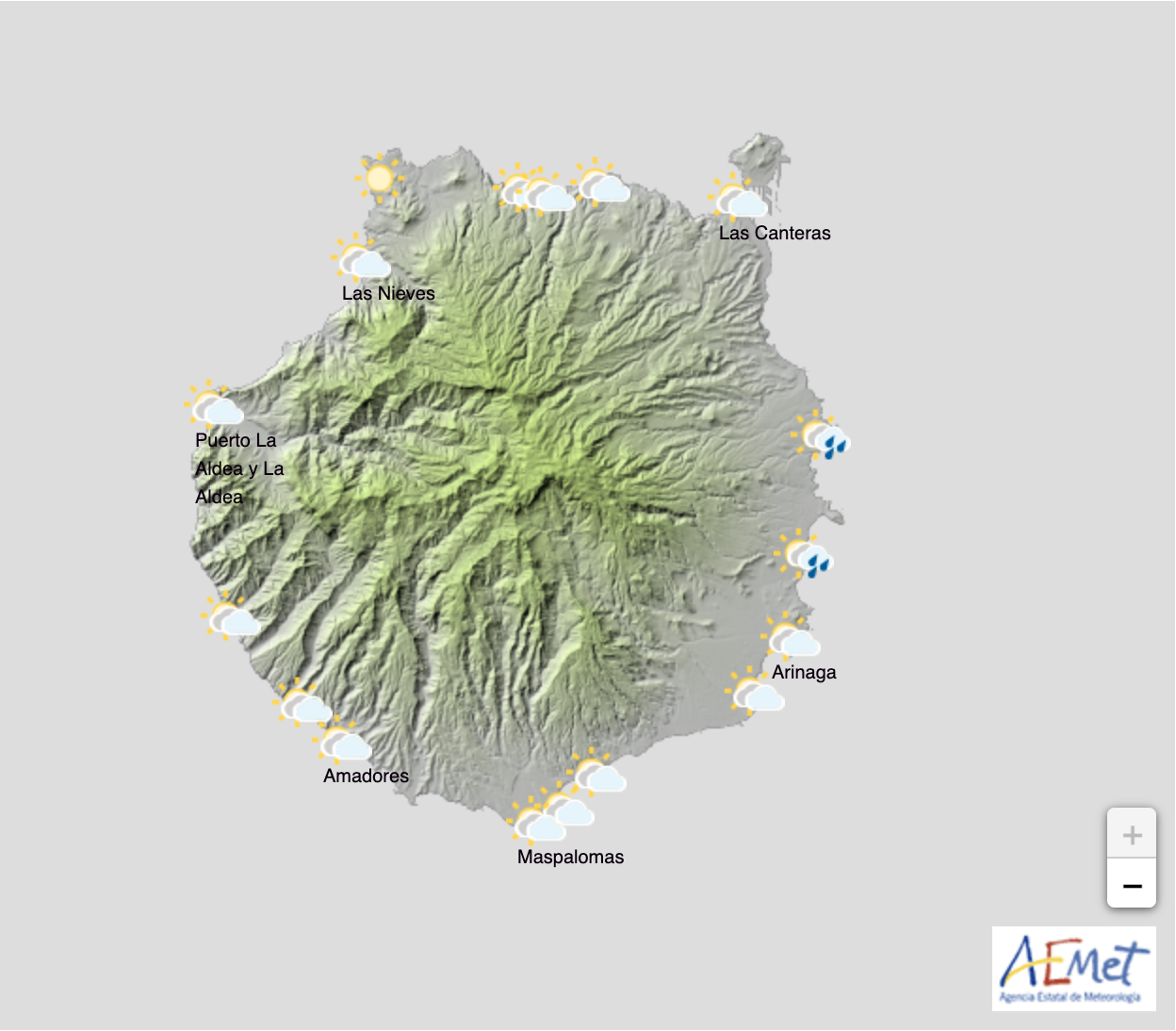

The Canary Islands stand at Europe’s southernmost frontier. While Western Sahara is just over 100km east of here, occupied and controlled by Morocco whose US military and diplomatic ties grow ever-stronger; the Mauritanian coasts, to the south east, are just 778 kilometres away; and Senegal is further south still, some 1,311km from here, almost exactly the same distance to the north separates Las Palmas de Gran Canaria from Cádiz. Even if it is not yet evident to everyone, the archipelago really is in the middle of all this.

This week an action plan, drawn up in Brussels, assessing the ongoing consequences of the war in Ukraine, gravely points to the likelihood of “a catastrophic famine” in the countries of North Africa. An internal report commissioned by the European Council warns that the tension Ukraine adds to the situation with food security increases the risk of triggering “new waves of migration to the EU” with Spain and Italy on the front line.

This week an action plan, drawn up in Brussels, assessing the ongoing consequences of the war in Ukraine, gravely points to the likelihood of “a catastrophic famine” in the countries of North Africa. An internal report commissioned by the European Council warns that the tension Ukraine adds to the situation with food security increases the risk of triggering “new waves of migration to the EU” with Spain and Italy on the front line.

The European Council estimate around 30% of global maize and wheat supplies come from Ukraine and Russia, with at least 20 million tons unable to leave Ukrainian ports and that 47 million more people will likely be affected by acute food insecurity in 2022

Vice-President of the European Commission, Josep Borrell, who is also the European Union High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, this week wrote:“For several decades, hunger was declining and the international community committed to end it globally by 2030 with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted in 2015. However, since then, the number of undernourished people has stopped decreasing and the COVID-19 pandemic has already made things much worse. The World Food Program (WFP) estimates that this number has risen from 132 million people before the COVID-19 pandemic to 276 million in early 2022 and 323 million today.”

Europe estimates that 40 million tons of cereal are blocked in the Black Sea ports

EU Member States this month managed to unblock progress on the New Pact on Migration and Asylum, just a few days ago, reaching an agreement on a voluntary solidarity mechanism for the distribution of refugees. It underlines that relocations should primarily benefit the countries within the Union that face landings after search and rescue operations both in the Eastern Atlantic – the Canarian route – and in the Mediterranean. There are those who believe this pact does not go anywhere near far enough, with “voluntary solidarity” having already so often failed to function as intended, leaving the countries and regions of first contact to try to cope with increasing arrivals.

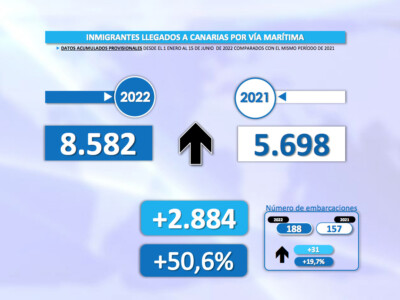

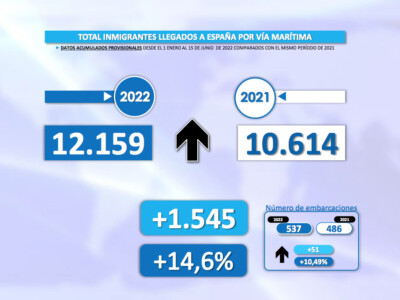

A total of 8,582 people have arrived already this year to the Archipelago, between January and June 15, which is 2,884 more people than during the same period last year, in fact 50.4% more; while the 3,478 maritime arrivals to the Balearics and Mainland are significantly lower (-26.7% year on year), the canary islands figures actually produce an overall increase of more than 14% for maritime arrivals, and nearly 20% overall, when you include arrivals by land. Even with the so-called “Good neighbours” treaty having been signed in April, between the Spanish and Moroccan governments, which entailed much greater controls over migrants leaving for Spain, the continued increase in numbers arriving to these islands has been a shock to those trying to deal with the consequences of these migratory flows. Perhaps less so for those trying to shift attention on to the origins and causes.

Despite Spain’s best efforts, recently, to work with Morocco on prevention, resulting in reports of much higher numbers of migrants now being stopped from leaving Moroccan shores on open boats, it seems the numbers attempting the crossing to this archipelago are still climbing. This comes even as Spain has appeared to perform an about turn, on their entrenched position of recent decades regarding Western Sahara, by offering tacit support to Morocco’s settlement proposals, which, at first glance, seem to disregard decades of concerted resistance from the native population, many tens of thousands of whom have lived in refugee camps for nearly 50 years now (represented by the Polisario government in exile, and cautiously supported by Algeria), as well as apparently discarding decades of opposition from the UN and other EU member states. It’s clear that much more will need to be done to try to stem the migratory flows, which have their origins in countries across the Sahel.

There are, too, many more reasons for concern in the region, with increased US military support for Morocco, and Algeria’s longstanding opposition to the nearly half a century of illegal occupation in Western Sahara, not to mention the now well-established plans for two major gas pipelines stretching from Nigeria to the mediterranean, both connected to Morocco, one straddling Algeria, and the other, Atlantic pipeline, set to connect 13 West African countries to the Nigerian gas fields, including Benin, Togo, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, Senegal and Mauritania, and through those territories to the mediterranean coast and then, it is planned, Europe.

According to a press release issued by the Australian company Worley, the company chosen to carry out the preliminary studies for the project and design the pipeline:

“When completed, the more than 7,000-kilometre-long pipeline, promoted by Morocco’s National Office of Hydrocarbons and Mines (ONHYM) and the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), will connect Nigeria to Morocco, cross 13 West African countries and extend to Europe. It will be the longest offshore pipeline in the world and the second longest overall”.

Here on the Islands, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs have not yet dismantled the camps they so hastily, and belatedly, set up in 2020 as a result of the migratory rebound (which had been warned of for at least a year prior). 23,023 individuals arrived on these shores, during the initial period of pandemic responses, compounding problems was a complete ban on international travel, with tourists unable to fly and migrants unable to leave. It was the largest surge of arrivals since what is known as “the crisis of the cayucos” back in 2006, when the Canary Islands received 31,678 migrants arriving on open boats and cayucos (small, open canoe-like boats). The Ministry has instead, quietly, launched improvement works to the Temporary Foreigners Care Centre (CATE) on Lanzarote, and to the main shelter for minors and mothers in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. And despite La Laguna Town Council’s announcements, on Tenerife, nor has the heralded closure of the old Las Raíces military barracks camp come to fruition.

With spaces available for up to 7,000 people across the island, and the estimated numbers of migrants living in those camps having fallen to less than 1,000 by the beginning of this year, it seems clear that the Government of Spain is now doing what it can to prepare for a further surge.

According to the FAO – the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation – the number of people in need of food assistance in West African countries rose from 7 million to 27 million, over the last decade and a half, and estimates that if aid is not articulated internationally and supplied urgently, that number could grow by another 10 million or more by the end of this summer. The picture is getting ever more complicated.

The priority set by the European Commission, in its logistics support plan, rests on the search for export routes so that the cereals currently blocked in the Black Sea might instead leave by train or by road, and so can be exported. Both Ukraine and Russia – against whom multiple sanctions condition their international trade – are among the main grain exporting countries in the world. Ukraine distributes around 10% of the world’s wheat, 13% of barley, 15% of millet and more than half of all sunflower oil, according to data provided by the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies to Casa África. Millions of tons of food – Brussels calculates 40 million – are being stored, waiting for a fluid exit to be agreed, taking into account that up to five million tons per month would usually have left by sea. African countries imported 44% of their wheat from Russia and Ukraine between 2018 and 2020, according to UN figures, quoted by Spanish language daily La Provincia.

The de facto blockade of food supplies brings with it worrying increases in food prices particularly in the more fragile regions, such as the Sahel. The African Development Bank has reported a 45% increase in wheat prices on the continent on top of a 20-30% increase in the overall price of food in the last five years throughout West Africa.

Add to this, on top of soaring fuel prices, the shortage of goods transport containers, that became apparent around the globe with the start of the covid-19 pandemic. This will hamper any efforts to establish alternative supply sources, which even if they are identified would take many months or, more likely, years to be established. Meanwhile people will still have to eat.

To make matters worse, even before the invasion of Ukraine, on February 24, the World Food Program had been warning that this would be a difficult year: China, the world’s largest wheat producer, is facing one of the worst harvests in its history after floods that last year devastated the central province of Henan; and India, ranking second in the world, has just paralysed exports due to the severe drought that the country is suffering from with crop yields much reduced. This has not been caused by the situation in Ukraine, the WFP have been warning for some time of a starvation catastrophe, but war has now accelerated the worst predictions for the foreseeable future.

Worse still, there is also a problem with our trying to increase local production. Russia and its ally Belarus are two of the world’s largest exporters of fertiliser, which is crucial for intensive farming and production, let alone any increases to local production, and both countries are now limiting sales. At the same time, the rise in energy prices, further exasperated by the war, has led to the closure of large factories in Europe which might otherwise have sought to fill the gap in the global fertiliser supply.

This is a perfect storm, with no clear solutions. We are going to have to weather it, and help as many as we can. What is clear is that simply disagreeing with migration is not going to make it go away.

Paying Morocco to stop hungry people getting into boats, is not going to stop them being hungry, and it is certainly not going to dissuade them risking what little they still have, including their lives, in the search for security.

In the absence of any clear plan to effectively tackle the root causes of migration, and certainly not any time soon, we are going to need to figure out how we, as a community, will deal with millions of people on the move from West Africa, and tens of thousands, possibly more, arriving on these shores.

Either we will value our humanity, and try to find positive and constructive ways to react, working with a situation far beyond our control; or we will allow misinformation, ignorance and anger to drive whatever happens next. Misplaced anger rarely solves hunger but it can certainly put communities at real risk of tearing themselves apart, never mind its destructive potential, increasing harm to all involved and further putting lives and livelihoods at risk. We need to think calmly and work to build communities that are resilient to change. You can’t fight the ocean, but you can learn how to fish.

Timon .:.

Canary Islands President Victor Torres demands “shared solidarity” from Europe

The Regional President called for “shared Solidarity” from the rest of Spain’s autonomous communities, and delivered the same message on Friday to the European Committee of the Regions’ Committee on Citizenship, Governance and Institutional and Foreign Affairs (Civex) in a meeting to address the impact of migration and the need to improve the support from European institutions for local and regional authorities.

The Regional President called for “shared Solidarity” from the rest of Spain’s autonomous communities, and delivered the same message on Friday to the European Committee of the Regions’ Committee on Citizenship, Governance and Institutional and Foreign Affairs (Civex) in a meeting to address the impact of migration and the need to improve the support from European institutions for local and regional authorities.

President Torres, speaking by videoconference, valued the recent advances to unblock reform of the European Pact for Migration and Asylum and presented to the meeting the current migratory situation in the Canary Islands, a territory at the southern border of the EU, located less than 100 kilometres from the neighbouring African continent and “which has become the tragic protagonist of the Atlantic migration route, one of the most dangerous in the world.” The president put unaccompanied migrant minors at the very centre of immigration management. He explained, according to a statement, that the regional government has protected and cared for more than 2,400 unaccompanied minors in this situation, which has led to 50 centres being mobilised, until this year, costing the islands more than €70 million of their own resources.