José María Mañaricua, the president of FEHT, the Federation of Hotel and Tourism Entrepreneurs of Las Palmas, in this Sunday’s La Provincia, discusses the ongoing disagreement between government officials and business leaders regarding the extent of the tourism recovery on Gran Canaria after the pandemic. He presents his assessment of the situation on the island, highlighting the differing interpretations of the same data. According to Mañaricua, the vision of the business federation he leads emphasises the challenges faced by Gran Canaria in recovering its tourism sector.

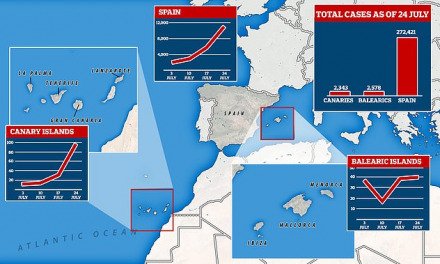

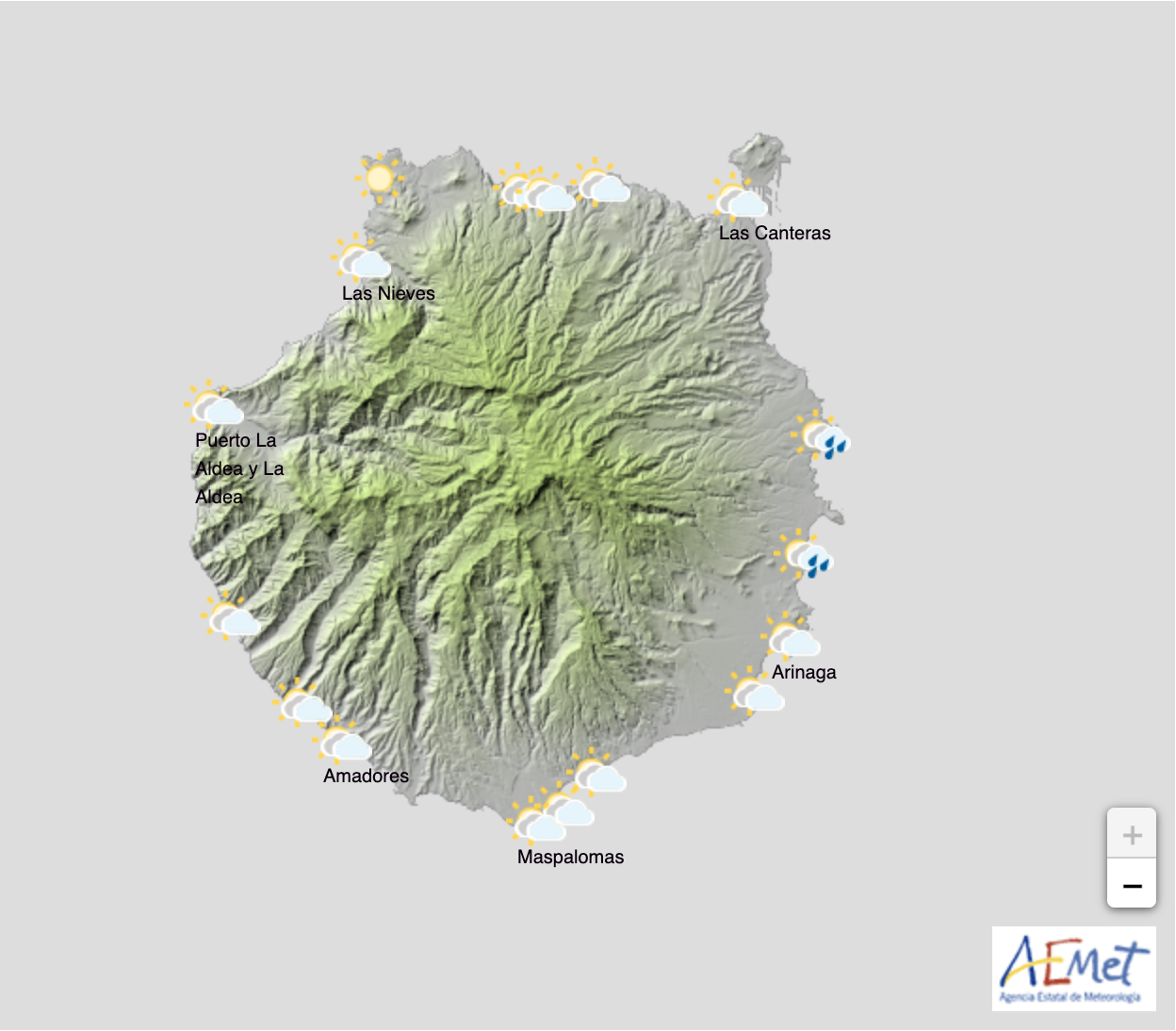

Comparing tourism statistics from 2019, which were already lower than those of 2018 and previous years, Mañaricua points out that Gran Canaria, along with La Palma, has not been able to regain its pre-pandemic tourism numbers. From January to July of the current year, Gran Canaria has seen a 1.1% decrease in foreign tourists compared to 2019. In contrast, other Canary Islands like Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, and Tenerife have seen increases ranging from 3% to 8.5%. This disparity raises concerns about Gran Canaria’s ability to truly recover its tourism sector.

Mañaricua criticises the lack of leadership from the Tourism Department of the Cabildo (the island’s governing body) in addressing critical issues such as the increase of resident housing in what he terms as “hotel areas”, loss of hotel capacity, and the deterioration of commercial centres. He argues that the island needs visionary leadership to address these challenges effectively.

In response to claims that tourists are spending more money than before the pandemic, Mañaricua questions how this can happen when outdated infrastructure, such as deteriorating commercial centres and beach services, fails to attract high-spending visitors. He highlights the need for investments in public infrastructure to support higher-end tourism.

Mañaricua also discusses the phenomenon of “residentialisation” in tourist areas. He states that Gran Canaria has lost around 35,000 non-hotel beds due to this trend. He emphasises the need for a comprehensive plan that differentiates between residential and tourist use in such establishments, as well as proactive efforts to renew tourism facilities.

Addressing the state of the island’s commercial centres, Mañaricua highlights the degradation and abandonment of these structures, particularly in the south. He proposes a Plan of Modernisation and Improvement (PMM) or regulatory changes to encourage the renewal of these centres, making them more attractive to tourists.

Discussing the conflict between tourism and the cement industry at Santa Águeda port, Mañaricua disagrees with the island Tourism Board’s stance, apparently, in favour of the cement industry. He advocates for combining fishing and tourism-related uses in the area while prioritising higher-quality accommodations.

Regarding the newly elected municipal government of San Bartolomé de Tirajana, Mañaricua urges coordination with the Cabildo and the Government of the Canary Islands to develop immediate PMMs, improve beach services, and renew commercial centres. He emphasises that San Bartolomé is a vital driver of Gran Canaria’s tourism and that its success affects the entire island.

Finally, Mañaricua addresses the Federation’s ongoing effort to prevent the demolition of hotels in Corralejo’s Dunas area, on Fuerteventura. He praises the Canary Islands’ assumption of coastal authority from the central government, emphasising the importance of preserving key hotels for the local economy and tourism sector.

In conclusion, Mañaricua’s assessment underscores the challenges Gran Canaria faces in recovering its tourism industry and highlights the need for proactive leadership and innovative solutions to revitalise the sector.