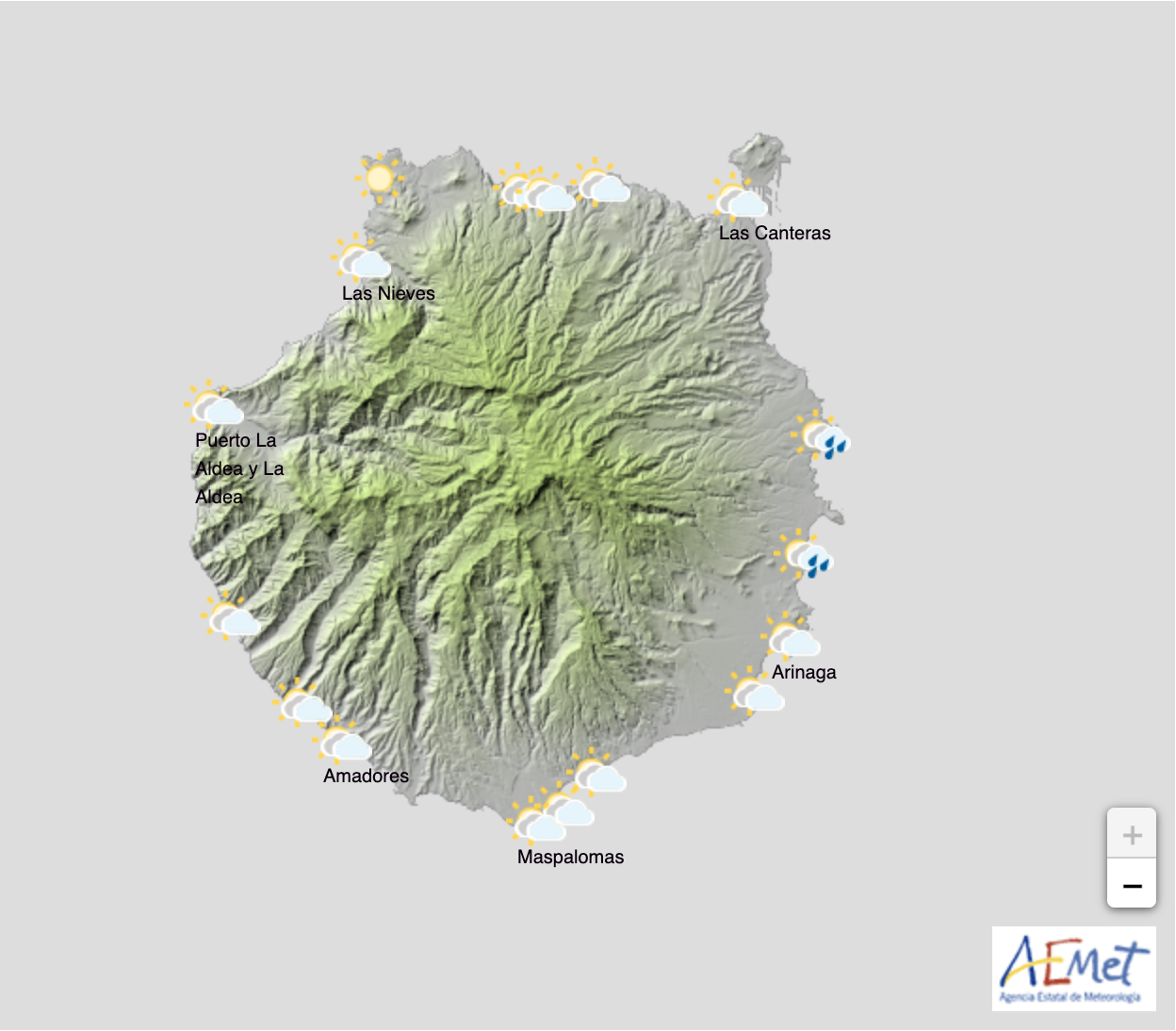

The Canary Island of El Hierro marks the last possible point of landfall for those who head west into the Atlantic Ocean from the coasts of Africa. Beyond it lies 4,500 kilometres of open ocean. The Canary Islands rescue services hold their breath, says Efe’s José María Rodríguez today in Spanish language daily La Provincia, whenever an open boat is discovered in the westernmost waters of Europe’s most southwesterly point, as they are probably adrift and for anyone still left alive on board, almost beyond their last chance for rescue, a desert of water awaits.

Sometimes these open fishing boats do cross the ocean, but no one survives such a crossing. At least Fourteen corpses, reduced to little more than bones, are currently being examined by a forensics team in Trinidad and Tobago, from a boat found in their coastal waters.

On Tenerife, 24 still recent graves, with anonymous tombstones, recall the fate of one group of migrants. It is a danger to which the thousands of young Africans who attempt to travel the Canary Route, towards some European dream, subject themselves in flimsy fishing vessels, to end up exposed to the harsh realities of the ocean: where death by thirst, surrounded by water, is still all too common.

On Tenerife, 24 still recent graves, with anonymous tombstones, recall the fate of one group of migrants. It is a danger to which the thousands of young Africans who attempt to travel the Canary Route, towards some European dream, subject themselves in flimsy fishing vessels, to end up exposed to the harsh realities of the ocean: where death by thirst, surrounded by water, is still all too common.

These 24 bodies were recovered from a boat found by chance, 500 kilometres from El Hierro on April 26. They had left Nouakchott three weeks earlier carrying about 60 occupants and less than a litre of water per head, thinking that they would reach the Canary Islands in three or four days. There were only three survivors.

There has not been a month in recent times during which one or two vessels have not disappeared from Mauritania on this route, the founder of one very active NGO tells Efe, alarmed by the number of boats that have been lost in recent weeks, with several hundred people on board, lives that have vanished. Or with a hundred at a stroke, as with a boat in M’Bour (Senegal) carrying 102 occupants, of which nothing more has been heard in more than a year.

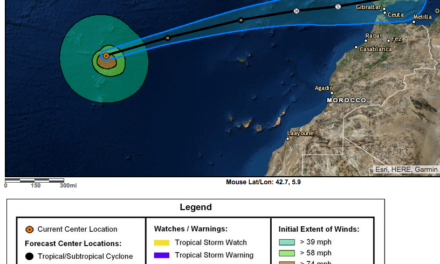

In most cases, these boats disappear without a trace, capsize, break up and are swallowed by the ocean. But, sometimes, rarely, the trade winds and the currents that make up the great oceanic churn manage to carry an intact cuyaco to the Americas, drifting the same route that Christopher Columbus inaugurated in 1492: from the Canary Islands, to the Caribbean sea.

Because, if they continue afloat, they are trapped by the Canary Current, which drives them relentlessly towards America, at a speed of 20 centimetres per second (17.28 kilometres per day), according to data from the Institute of Oceanography and Global Change at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. It is difficult to calculate because the drifts are erratic and the wind has influences, but a boat at the mercy of the currents can take six, seven, eight or more months to reach the Caribbean… It all depends on where their engines stopped.

In May 2006 a cayuco appeared in Barbados. It had set out for the Canary Islands from Cape Verde, carrying 47 young Senegalese, many months earlier, most likely at the end of 2005. Only eleven decomposed bodies were recovered from the vessel; the other 36 were lost, at some point along the more than 3,900 kilometres they travelled.

On May 15 of this year another boat was found adrift seven kilometres from Belle Garden, in Tobago. Among its boards, there were fifteen corpses, who it was initially thought might be Venezuelan emigrants.

But it has now become clear to the Tobago Police that this is a Mauritanian vessel. An inscription on the boat – possibly a license plate – and a mobile phone recovered from among the corpses. The tragedy of 2006 has once again been repeated and the currents have pushed a cuyaco from Africa to the Caribbean, this time travelling more than 4,800 kilometres, while its occupants were consumed with hunger and thirst.

Skeletal remains found in Tobago on board boat from Mauritania

The head of police in Tobago, which comprises the smaller of the islands that make up the nation of Trinidad and Tobago, confirmed to reporters that the boat had drifted ashore with at least 14 bodies on board.

He added that skeletal remains were stacked inside the boat and found floating near the island last Friday.

“The boat, according to our information, was believed to have been stolen and there is an investigation under way in the country,” William Nurse told reporters.

“We expect to finish [the autopsy] by today and, given the level of decomposition, we are not sure that we would be able to get a definite cause of death,” Nurse said. “It may be dependent on a toxicology report. If that is the case, we will wait on that before making a pronouncement.”

It remains unclear what caused the deaths of those on board, or whether the deceased were citizens of Mauritania.

“We cannot say whether the individual bodies were… citizens of Mauritania. The best way to respond to that is to do cadaver fingerprints, and having done that we might have secured identity,” Nurse added.

The cayucos of Mauritania do not set out for the Canary Islands with just 14 occupants. It would be a waste of space. Generally, they board 50 or 60 people, almost always young men, although lately there are usually one or two women on board (in the El Hierro boat, one of the three survivors is just a teenager).

Those who are missing, most surely perished of thirst and were thrown into the sea, while their companions were still able to deal with them. Others, writes José María Rodríguez, possibly committed suicide to end their agony and some perhaps died in fits of madness.

One of the survivors of the El Hierro cuyaco said that the first of his companions to jump into the sea said, just before falling overboard, that he was going to buy tobacco. It was his twelfth day of the voyage, after more than a week without food or water. And their story is no exception, it continues to happen, these are the ghost boats that probably no one will ever hear from again.

Timon .:.