Spain’s central government has clarified that the responsibility for covering the burial costs of migrants who die at sea rests firmly with local municipalities. This clarification comes in response to La Alcaldesa, O. Bueno, the current mayoress of Mogán on Gran Canaria, having recently declared that her municipality will no longer fund these burials.

The government cited a 1974 public health regulation that obligates all local municipalities to provide coffins for indigent or impoverished individuals who die within their jurisdiction. According to an official statement, the rule must be “interpreted according to its spirit and purpose,” as outlined in Article 3.1 of the Civil Code.

Although there is no specific legislation concerning those who die at sea, the government argues that the same public health concerns apply. Therefore, the responsibility still falls on the municipality, especially when the deceased are brought to Mogán, home to two maritime rescue vessels. The mayoress has also recently tried to have those maritime rescue vessels moved elsewhere, a demand that was met with a firm denial.

Previous Controversies

Previous Controversies

This is not the first time the incumbent Mogán administration has clashed with central government over migrant issues. In 2020, Mayor Bueno hurriedly ordered buses( with the help of a known local far-right activist) for around 200 migrants who had been released by police without warning from the overcrowded port. The migrants were transported then dumped in front of the headquarters of the Central Government Delegation in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, leaving them without food, resources, information or shelter. Residents of Las Palmas spontaneously came to the aid of those migrants, until buses could be organised to transport them back to the south where accommodation had already been organised for them. Bueno has also been at the centre of other related controversies, including opposing the accommodation of migrants in hotels left empty by the pandemic, and supporting xenophobic protests which attracted the attention and subsequent attendance of far-right Vox political leader Santiago Abascal.

PSOE Condemnation

Luc André Diouf, a PSOE deputado (similar to a member of parliament), knows the issues well, having himself arrived to these shores back in the 90s prior to getting involved in politics. Highly educated, a speaker of multiple languages, with personal experience of the current system of migrant processing, he has denounced Bueno’s refusal to fund migrant burials as simply “racist.” In a social media post, Diouf accused her of “shirking her responsibilities due to racism,” questioning her understanding of the laws regarding the certification of deaths.

Diouf took seriously the outcry from a small but loud section of the Mogán population, following the crises of 2020-2021, and took the time to visit the town of Puerto Rico de Gran Canaria back in January as part of a PSOE outreach to discuss all the issues raised, unfortunately very few people were able to attend, and not one of the anti-migration protesters who had so fervently marched through the town at the end of 2020 was available to address the situation with him. Nonetheless mister Diouf was clear and unequivocal in his admiration for Spain and its adherence to human rights and European values, and the need for more compassionate responses towards strangers who arrive on these shores.

Financial Concerns

According to sources connected to funeral services, the cost of burials ranges between €600 and €1,000. Mayor Bueno, whose own tenure has been marked by police investigations, the emptying of the municipal coffers, fines and repeated accusations of corruption, states that these are funeral expenses that would be deducted from the taxes of her constituents, criticising the central government for not showing any interest in the matter.

Broader Impact

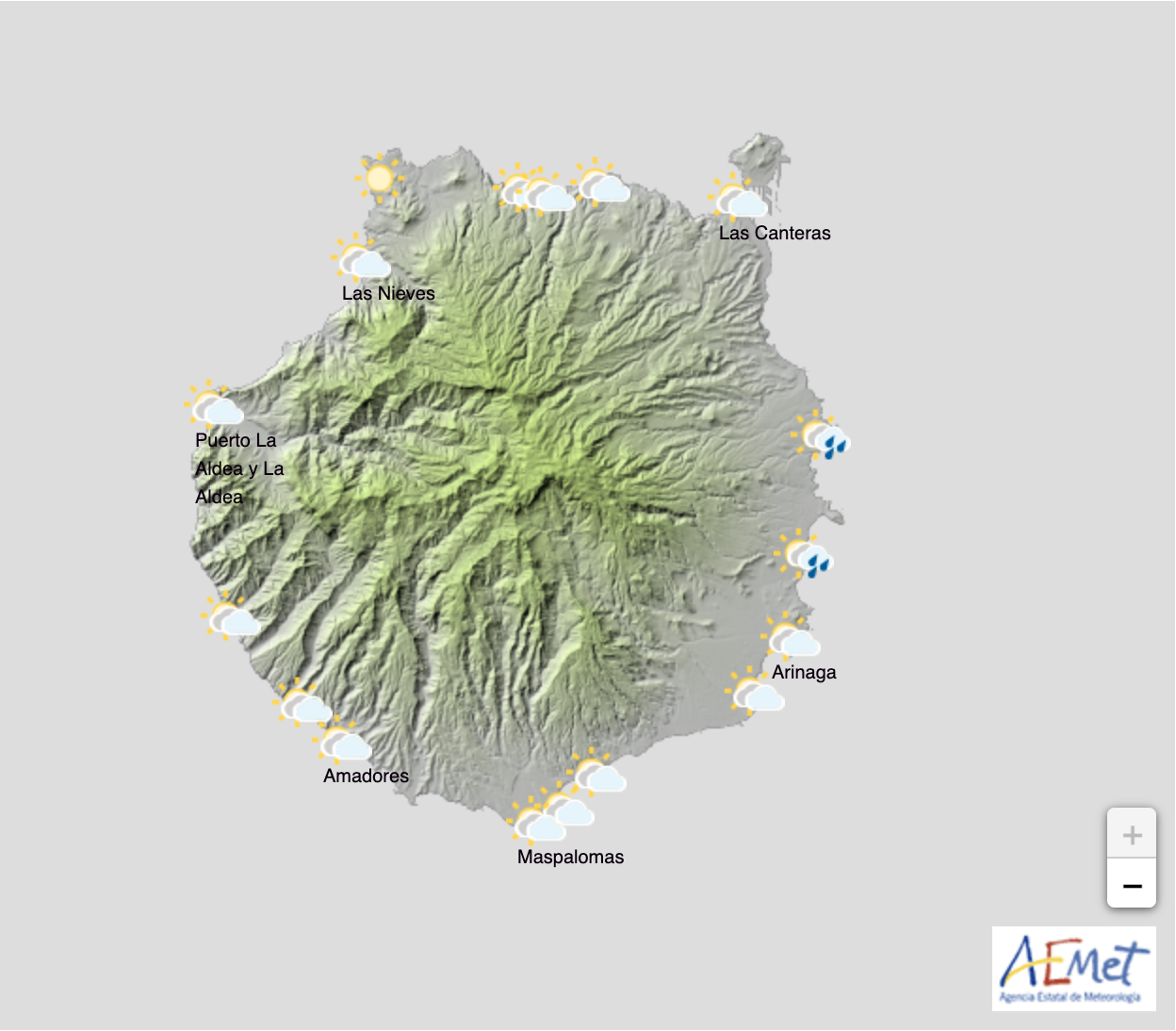

Bueno’s stance raises questions about the intersection of municipal responsibilities and humanitarian considerations, especially given the unique geographic context of the Canary Islands. Her recent announcement also underscores the tension between local governments and the central administration in handling the ongoing migrant crisis, an issue that is expected to become more prominent as more and more boats arrive through October and November taking advantage of the calmest tides of the year.

The debate also happens within the backdrop of previous demands by Bueno to remove the maritime rescue boats stationed at Mogán’s Arguineguín dock, claiming they hinder commercial and tourism activities. The Central Government have reminded her that these services are based at what are considered to be the best locations to protect public safety and the safety of all maritime traffic, with tourism being a lower priority to Spain’s commitment and duty to prevent death and injury at sea.

While the central government maintains that the local authorities are legally obligated to handle migrant burials, the mayor’s refusal has sparked both legal and ethical debates, drawing criticism from opposition parties. The tension between Mogán and Spain’s central government in Madrid adds another layer to the ongoing challenges in managing migrant affairs in the Canary Islands, and once again places Bueno in the spotlight of controversy.

The questions we should perhaps be asking is how many migrants die trying to get here, not how many should we be expected to bury, though it would be interesting to know how many migrant burials Mogán has actually had to pay for.

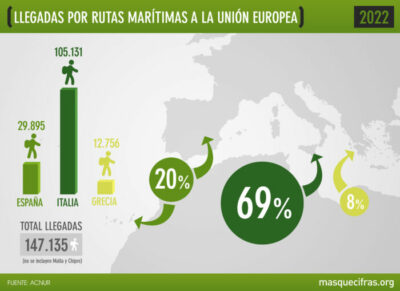

Less than 10% of migrants claiming asylum in Spain are from Africa

While no figures have been offered on quite how many burials Mogán has been expected to oversee, it is known that The Canary Route is the most dangerous migratory route in the world, with untold hundreds and perhaps even thousands of people never being heard from again once they launch themselves out into the Atlantic Ocean in the hope of a better future.

Those that do arrive here are the lucky ones, many will be returned to their countries of origin, or processed for asylum claims. Those arriving on boats represent only a small proportion of the numbers seeking refugee status every year, the vast majority of which originate in South America and arrive here by other means, mainly from Venezuela and Columbia. Most African migrants claiming asylum last year were from either Morocco or Mali, though a significant increase is expected this year due to political instability in countries like Niger and Senegal.

- Maritime Migratory Routes to Europe

- Proportion of Asylum Claims Granted in Spain

- Nationalities of Asylum Claimants in Spain