Many in Spain celebrate the national day, October 12, as a day for all Spaniards to revel in Spanishness, and remember an empire, replete with displays of military might, with marches and the waving of flags coloured blood and gold.

For many, it is not a day of celebration but a time worth spent remembering countless millions whose lives were so irrevocably affected after the arrival of one lost adventurer, who managed to find a small Bahamian island, an ocean away from the newly united kingdoms of Spain, and their, just previously acquired, first colonial conquests.

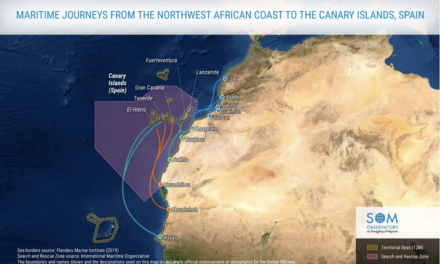

The Canary Islands were still four years from being completely brought under control when 3 tiny ships, “La Niña”, “La Pinta” y “La Santa María” stopped in Spain’s first Atlantic colony, almost 100 years since French mercenaries had been first given permission to take them as possessions for Castile. The church had sent Franciscan priests from Mallorca 50 years earlier, who lived among the people of Telde for many years, before something caused them all to thrown to their deaths into a volcanic tube at Jinamár. A Norman adventurer, Jean de Bethencourt, was given license to conquer the islands, funding the expedition himself he conquered Lanzarote, Fuerteventura and El Hierro without too much resistance. But he had been unable to take the island of Canaria. When he landed at Arguineguín, a failed negotiation and the battle that followed left Gran Canaria’s King Artemi Semidan dead and the Normans in retreat, proclaiming the fierce natives of the island to be a greater people than had previously been imagined, dubbing the island Great Canaria. The Spanish would not attempt it again for another three quarters of a century, landing in 1478 with nothing less than total domination in mind.

By 1492 Gran Canaria’s native people, the Canarios, had been largely subdued, having officially capitulated in 1483 following the battle of La Forteleza. Those who would not follow the example of their nobles and convert, were taken for slaves, or simply murdered. The genoese merchants who funded the expedition, along with the church, were awarded huge swathes of land from which to grow food and the highest value luxury product of the day, sugar. The Catholic monarchs, their minds now set on new horizons, had sent wave after wave of men in ships to eventually and mercilessly control a native population which had a complex and advanced culture; many centuries, if not thousands of years in the making. Their society was all but eradicated. Spain’s first Atlantic colony had been founded. The brutality and violence of that conquest had set the metre and the method for the conquests that were to follow…

Gran Canaria’s last true king, Guanarteme of Gáldar, Tenesor Semidan, had been fatefully captured just two years in to the bitter fighting. He was then sent by sea, on a journey that must have been beyond anything he’d ever previously imagined, to appear before the monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, on the Iberian peninsula, where he undoubtedly witnessed first hand the terrible might, grandeur, weaponry and vast numbers of the invaders. He would have now understood what he was up against.

Gran Canaria’s last true king, Guanarteme of Gáldar, Tenesor Semidan, had been fatefully captured just two years in to the bitter fighting. He was then sent by sea, on a journey that must have been beyond anything he’d ever previously imagined, to appear before the monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, on the Iberian peninsula, where he undoubtedly witnessed first hand the terrible might, grandeur, weaponry and vast numbers of the invaders. He would have now understood what he was up against.

After some time, with his queen and offspring at stake, he was returned to his island home, having had to make an impossible choice between his noble heritage, his people, his kingdom and his family. He had agreed to become a vassal king signing the Calatayud Pact with Fernando the Catholic he became a valuable ally to the Castilians. In what some historians see now as a bid to avoid complete annihilation, in the face of insurmountable odds, the last king of Gáldar returned having converted, baptised as Fernando Guanarteme, forced to act as mediator with his own nobles, a peacemaker, a collaborator and military advisor to the invaders, and diplomat-negotiator for the very survival of a people already weary and worn by sickness, food scarcity and incessant attack. On 29 April 1483 Guayarmina Semidán, considered to be queen of Gran Canaria, surrendered at Ansite Fortress (Tunte). On the same day Chief Bentejuí and his shaman-advisor Faycán, committed one final act of resistance by jumping from a cliff, rather than be captured, while shouting Atis Tirma (for my land).

To many of his own people Fernando Guanarteme was, in the decades and centuries that followed, simply seen as a traitor. Brutality, disease, murder and enslavement had taken their toll, and Gran Canaria finally yielded its resistance after 5 long years of fighting, to become a staging post for the conquest of the other island peoples, fighting continued in vain for more than a decade.

It was to this backdrop that the adventurer, perhaps of Portuguese birth, arrived on Gran Canaria in 1492. Ferdinand and Isabel were celebrating the expulsion of the last of the North Africans who had ruled Iberia for more than 700 years, ridding themselves, as they saw it, of the heathen Jews and Muslims who had controlled the peninsula, the apocryphal “Reconquista” was complete and now theirs was a thirst for new lands, new conquests and new routes to untold riches. The template for conquest was clearly set out in the example made of these “fortunate islands” and their people. Tenerife was still yet to fall.

The united kingdoms of Aragon and Castile now had a tried and tested system for the transfer of military might, governance, agriculture and commerce to far off and soon to be discovered lands, ripe in their eyes, as well as those of Rome, to be conquered, colonised and, ostensibly, converted, for the glory of their God. Over the century that followed Spain was to become the wealthiest super power that Europe, or the world, had ever known.

Once Tenerife had been subdued, with the invaders still conscious of his birthright and status, Fernando Guanarteme, it seems, died under mysterious circumstances, never to return to Gran Canaria, his body was buried in an unknown grave. His daughters forced to marry their captors, in an effort to further their legitimacy as rulers.

Contrary to popular belief most sailors already knew that the earth was not flat. Cristobal Colon (that’s Columbus to most English speakers) was no hero, nor a genius and he almost certainly was not Genoese as so many have claimed over the centuries.

Though many still may celebrate him as “The Discoverer” his voyages across the Atlantic significantly changed world history, and tolled a death knell for millions upon millions, for many centuries to come. His own cruelty as governor of the lands he took, and that of his men, set in motion some of the most heinous known crimes in history against a peaceful native population, many of the effects of which are still incomparable, and still being felt, today, still not understood, still not healed. So brutal was he, even for the time, that he was stripped of his titles after just a few years.

Nonetheless, his legacy, seen through the lens of history, not only left devastation, but also created a bond between cultures across the Atlantic that for many continues to this day. Understanding this legacy continues to raise passions, both for and against, the facts of what really happened on October 12 1492.

_________________-

Opposition to Columbus Day dates back to the 19th century after the very first known celebrations occurred, some 400 years after the actual events, leading to nativist protests who sought to avoid association with the white immigrants and the Knights of Columbus. Some anti-Catholic protesters feared that the day was being used to expand papal influence. By far the more common opposition today, criticising both Columbus’s and other Europeans’ actions against the indigenous populations of the Americas, did not gain very much traction until the latter half of the 20th century. World Indigenous Peoples’ Day has been adopted by various countries and post colonial populations.

Many now believe the name “Columbus”, thought to have been of Genoese origin, was attributed to him mistakenly in one of the very first written accounts of his journeys, and so most in Europe incorrectly learned the mistranscribed name rather than his original Cristobal Colón, as he is still known in Spain and Portugal. He may have originally been from a Portuguese noble family, and there is evidence he had an uncle, or similar, with some small influence in the courts of the Catholic Monarchs, of Castile and Aragon.

It had long been known that the earth was not flat, and it was the Portuguese who had first mastered the Volta do Mar, which allowed them to sail further and further south, before, counterintuitively, heading west out into the Atlantic so as to make the return journey to Europe.

During his first voyage in 1492, after stopping for repairs on Gran Canaria, Cristobal Colón reached the New World, instead of arriving in Japan as he had intended, landing on an island in the Bahamas archipelago that he named San Salvador. Over the course of three more voyages, he visited the Greater and Lesser Antilles, as well as the Caribbean coast of Venezuela and Central America, claiming all of it for the Crown of Castile. He claimed, until the day he died, that he had discovered a new route to India.

Colón is credited with establishing and documenting these routes to the Americas, though it is now known he was not the first white man to reach the continent. He was preceded by at least one Viking expedition, led by Leif Erikson in the 11th century. Moreover, Colón’s voyages led to the first lasting European contact with the Americas, inaugurating a period of murder, subjugation, exploration, conquest, exploitation and colonisation that lasted several centuries. These voyages thus had an enormous effect on the historical development of the modern Western world. He spearheaded the transatlantic slave trade and has been accused by several historians of initiating the genocide of the Hispaniola natives. Colón himself saw his accomplishments primarily in the light of spreading the Christian religion, and of course his own self-aggrandisement.

The indigenous people he first encountered, likely the Lucayan, Taíno, or Arawak, were peaceful and friendly. Noting their gold ear ornaments, however, Colón took some of them prisoner and insisted that they guide him to the source of the gold.

In his journal of 12 October 1492, he wrote of them:

“Many of the men I have seen have scars on their bodies, and when I made signs to them to find out how this happened, they indicated that people from other nearby islands come to San Salvador to capture them; they defend themselves the best they can. I believe that people from the mainland come here to take them as slaves. They ought to make good and skilled servants, for they repeat very quickly whatever we say to them. I think they can very easily be made Christians, for they seem to have no religion. If it pleases our Lord, I will take six of them to Your Highnesses when I depart, in order that they may learn our language.”

Columbus remarked that their lack of modern weaponry and metal forged swords or pikes was a tactical vulnerability, writing, “I could conquer the whole of them with 50 men, and govern them as I pleased.”

There are many strands of criticism, which are interrelated. One criticism refers primarily to the treatment of the indigenous populations during the European colonisation of the Americas which followed the discovery. Some groups such as the American Indian Movement have argued that the ongoing actions and injustices against Native Americans are masked by these positive myths and celebrations. These groups argue that the legacy has been used to legitimise these actions.

Made governor of these new lands, reports of his tyranny grew. Colón once punished a man, found guilty of stealing corn, by having his ears and nose cut off and then selling him into slavery. Testimony and reports told how Colón, on another occasion, congratulated his brother Bartolomeo for “defending the family” after he had ordered a woman paraded naked through the streets, and then had her tongue cut out, for suggesting that Colón was of lowly birth. The documents also describe how Colón put down native unrest and a revolt by first ordering a brutal crackdown in which many natives were killed and then paraded their dismembered bodies through the streets in an attempt to discourage further rebellion. “Colón’s government was characterised by a form of tyranny,” Consuelo Varela, a Spanish historian who has seen the documents, told journalists. “Even those who loved him had to admit the atrocities that had taken place.”

Since 1987, Spain has celebrated the anniversary of his arrival in the Americas as its Fiesta Nacional or “National Day”. Previously Spain had celebrated the day as Día de la Hispanidad, emphasising Spain’s ties to the international Hispanic community. In 1981 a royal decree established the Día de la Hispanidad as a national holiday. However, in 1987 the name was changed to Fiesta Nacional, a day of national pride and October 12 became one of two national celebrations, along with Constitution Day on December 6.

Spain’s “national day” had moved around several times during the various regime changes of the 20th century; establishing it on the day of the international celebration of “Discovery” was part of a compromise between conservatives, who wanted to emphasise the status of the monarchy and Spain’s history, and Republicans, who wanted to commemorate Spain’s burgeoning democracy with an official holiday.

Since 2000, October 12 has also been Spain’s Day of the Armed Forces, celebrated each year with a military parade in Madrid. Other than this, however, the holiday is not widely or enthusiastically celebrated in Spain; there are no other large-scale patriotic parades, marches, or other events, and the observation is generally overshadowed by the feast day of Our Lady of the Pillar or treated simply as a national day of rest and reflection.